Open data 10 years in Finland: routine and party

In the autumn of 2009, HRI saw the light of day and the first open data application competition Apps For Democracy was arranged. The first decade of open data is celebrated in Finland on 8–10 October 2019. In ten years, the enthusiasm of the pioneers of open data has made opening data a routine practice, but there is a lot to be done in the future as well.

In the summer of 2009, open data all-rounder Antti Poikola was busy. The Aalto University researcher had agreed to be in charge of the organisation of the first open data application competition. Apps For Democracy was a competition for applications, which made use of public data sources. “There were sponsorships, but then it became obvious that we did not have open data”, recalls Poikola, who now works as a Data Economy Specialist at the Technology Industries of Finland.

Even though Finland’s progressive legislation concerning the openness of government activities ensured the openness of documents, the data was not available on the web, at least not in machine-readable format.

There was still something. Architecture student Peter Tattersall caught an interest in the competition and completed his Tax Tree work for the idea category of the competition. “I went through all the data sources that I could find. I noticed that economic data forms a hierarchic structure, which can be portrayed in the form of a tree”, tells Tattersall, who runs Hahmota Oy, which specialises in data visualisation and refinement.

The lack of open data had been noticed at the cities in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area, which own considerable datasets. Director of the City of Helsinki Urban Facts Asta Manninen had received a commission from the mayors in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area concerning a regional data vision for the year 2020. The vision document, completed in summer 2009, included a proposition about opening public data of the cities for public use, free of charge. “In the compact vision, I ended up proposing the establishment of a joint Helsinki Region Infoshare service for the cities”, says Manninen, who is now enjoying her retirement days.

Open data year zero

The year 2009 marked the start of the open data movement in Finland. While visiting Finland, Peter Corbett gave a sales pitch about Washington’s data openings and successful Apps For Democracy application competition, which encouraged to do the same in Finland. Ending up working for the Somus research project was a momentous experience about the openness of data for Antti Poikola. The term “open data” was also mentioned in the research plan for the project, which focused on the utilisation of social media in public administration. Poikola found out about the project through a channel on the Finnish micro blogging service Jaiku. “Had the project application been made in the traditional way, I would have never heard of it.”

However, the research plan written jointly by Finnish social media pioneers on the web was available for anyone to see, and Poikola, who had taken an interest in the topic, was hired as a researcher for the project.

Many people interested in the openness of data met for the first time at the Apps For Democracy award ceremony in Tampere. Peter Tattersall’s idea to visualise income and expenditure of public organisations using a tree metaphor proved successful. The result was the first prize in the idea category of the competition – and the start of a career change. Three years later, architecture had changed to visualisation of data and Tattersall established a company to commercialise his skills.

The competition coordinator Antti Poikola’s discussions with the winners confirm a previous observation: the lack of open data was acute. Poikola did not hesitate, but proposed writing an instructional book for the Ministry of Transport and Communications, which sponsored the competition. The financing was granted and the instructional book Julkinen data – johdatus tietovarantojen avaamiseen (Public data – introduction to opening data reserves) by researcher trio Antti Poikola, Petri Kola and Kari A. Hintikka was published in spring 2010. For many, the manual has been the first insight into the world of open data.

As the Director of the City of Helsinki Urban Facts, which was responsible for the City’s statistics, archives and research activities at that time, Asta Manninen had already become familiar with the winds of openness, which were blowing around the world. The Australian statistics authority had done important pioneering work by analysing how the openness of data would go with official statistics, which are controlled by different acts, standards and very rigid privacy protection. “American cities, such as Washington, New York and Chicago, were once again among the leaders in the development of applications that make use of open data”, says Manninen.

When the Mayors’ meeting showed the green light for regional data visions, Asta Manninen started working. The work was backed by an established actor in the digital world, the City’s development company Forum Virium Helsinki, which named Ville Meloni the Project Manager of HRI. Asta Manninen allocated personnel resources from the Urban Facts to the HRI project.

So why was the joint data opening project parked at the City of Helsinki’s Urban Facts? “Helsinki’s Urban Facts was a more than 100-year-old organisation, full of knowledge, data management and statistics databases in fine shape”, explains Asta Manninen.

Many other countries had to start from scratch, by sorting out what kind of data the organisation actually was in possession of. “The Urban Facts had world-leading expertise, the cities of Espoo, Vantaa and Kauniainen had excellent capabilities to open data and we had the supportive backing of the City managements. We got off the mark quickly.”

The HRI service was established rapidly. The first alpha version was completed in 6 months after the initiation of the project, in December 2010. Ville Meloni and Urban Facts’ Pekka Vuori presented the HRI’s data contents for the first time to the public at the official launch event of the service at the Helsinki City Hall in March 2011. The first Finnish open data catalogue that was published on the web brought hundreds of datasets concerning the Helsinki Metropolitan Area available to everyone, free of charge. “First, we tried it on a small scale, then bigger. We published alpha and beta versions of HRI in fast pace. This was an entirely new way of doing things at the City and it suited us well”, remembers Asta Manninen.

The example set by the Helsinki region in opening data soon got followers, when Tampere and Jyväskylä opened their own open data websites. In 2011, the Finnish government published its decision in principle about public administration digital data: the main rule is that public administration dataset should be available openly and free of charge.

Finland rose to the front row

In 2012, open data started growing fast in Finland. The world’s biggest open data event Open Knowledge Festival brought together more than one thousand visitors from a hundred different countries to Helsinki. Antti Poikola and other open data enthusiasts founded Open Knowledge Finland, which gathered Finnish open data hobbyists and experts together. OKF is part of the world’s largest open data community, Open Knowledge Foundation.

Open data became a topic of discussion. The Finnish Information Processing Association gave the 2012 IT trendsetter of the year award to National Land Survey’s Antti Rainio, who is a renowned proponent of open data.

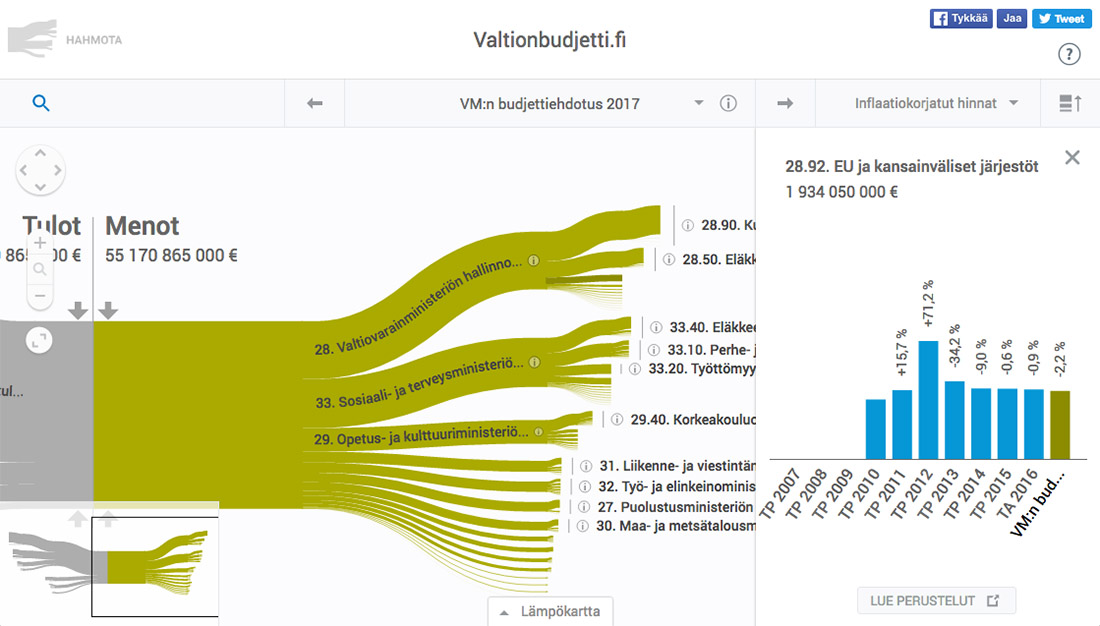

Peter Tattersall’s company made the tax tree into a vendible product, which provides a quick overview of a municipality’s, city’s or government’s spending. The first paying customer was the City of Hämeenlinna.

Open Knowledge Finland’s operations soon expanded to new areas and inspired new people to join in. One of the OKF spin-offs was the MyData movement, which wants to move personal data into the citizens’ own possession. The annual MyData conferences arranged by Antti Poikola and other initiators soon attracted a thousand participants to Helsinki from different parts of the world.

Finland, and especially the Helsinki region, received a lot of international attention. Asta Manninen received piles of invites to European cities and international conferences to talk about the HRI project. “We were quite stunned about all the attention”, tells Manninen.

Antti Poikola’s most fond memory from the open data upswing is the fight for the opening of Finland’s map data. At the time, the National Land Survey was a pioneer of opening data in the state administration. Under the leadership of Antti Rainio, it had prepared the opening of its own spatial data to the citizens, free of charge. However, the budget department at the Ministry of Finance was against the project as for the Government it would have meant a loss of income of several million euros from the sales of data. “It was a feat of strength by the open network. In the network, we prepared a question for the Parliament’s question time asking why the Ministry of Finance opposes something that has been agreed upon in the government platform and we did the background memos.”

Member of Parliament Oras Tynkkynen asked Minister of Finance Jutta Urpilainen about it in December 2011, when at the same time the EU Commission had just estimated that the benefits of opening data were worth 140 billion euros. The Yle people of the Open data network made the question which concluded the question time into its own topic on YLE Areena, and Antti Poikola’s sharp blog text about the topic attracted 5,000 readers in a day. Minister Jutta Urpilainen decided to support the openness of data, the Ministry’s budget department changed its mind and the National Land Survey’s spatial data was opened for public use, free of charge.

Additional resources needed

The first decade of open data in Finland is celebrated in October 2019. Open data has become an obvious thing, and the open data movement is not in the public eye like it was back in the day. “The pioneer enthusiasm may have worn off”, admits Poikola. When a couple of years ago, Finland was the wonderland of open data, now others have caught up. “Finland has lost its pioneer status in opening data”, notes Antti Poikola.

Opening public data has not always progressed in the way the supporters had hoped some years ago. “The start was quick, but the vigour ceased. The government had an open data programme, but when it finished, few resources have been put towards it since then”, analyses Poikola. He hopes that the work will be revitalised during the current Government’s term. The new budget proposal looks good in this context. More money will be allocated to the furthering of digitalisation and opening data in 2020.

The everyday of an entrepreneur in the field has not always been glamorous either. Peter Tattersall tells that the feedback that Tax Tree got in the Apps For Democracy competition should have been paid more attention to. Many were suspicious whether the public administration is ready for such openness, to publish its economic data for everyone to see, in an easily readable format. Even though Tax Tree found some clients from municipalities and government agencies, there are a lot of organisations where openness is not the primary course of action.”

The Tax Tree did not become the hit product that some had expected, but for Peter Tattersall it was the first step towards increasingly interesting projects. Nowadays, Hahmota Oy provides tools and consulting, where quantitative and qualitative data is refined to support the administration’s decision-making.

HRI did not slow down

However, in the Helsinki Region, the speed has not slowed down. HRI has started a knock-on effect, which shows even in Helsinki’s City Strategy. The journey towards the most functional city in the world cannot be done without a sturdy digital foundation. Helsinki intends to be a leading city in the world when it comes to opening and utilising public information. It brings us quite a positive pressure to keep on working for the openness of data”, tells HRI Project Manager Tanja Lahti.

The world’s best digital city is built according to the city’s new digitalisation programme and by opening interfaces into the City’s data systems. They enable fluent transfer of data between systems and opening public data for everyone to use.

Tanja Lahti and Planner Hami Kekkonen have noticed that opening the City’s data requires a lot of footwork. The data owners have to be assured of the benefits of opening data. One of HRI’s success concepts has been the data opening trainings arranged for City employees. “Sharing good practices has been another good course of action. For example, HRI’s training materials have been utilised by a lot of others as well and the articles published on the website have increased the understanding of open data.”

Open data in everyday use

It started with WWW

30 years ago, in 1989, the concept of open data did not exist, but a lot of groundwork was already being done around the world. In 1989, a researcher at the centre for scientific research CERN Tim Berners-Lee, later known as the developer of the World Wide Web, wrote the first http web address on his work station. Antti Rainio, who made his mark as an opener of data at National Land Survey, proposed in the Maankäyttö magazine, that data should be opened with tax-payer money: “Data should not be priced according to the wealthiest clients.“

Check out the history of open data in Finland since 1989 on the HRI website!

Even though it has not always been so great, the openness of data has taken giant leaps in Finland in a decade. “Nowadays, it is deemed obvious that data is available”, ponders Peter Tattersall.

Open data has become an everyday thing. Today, Peter Tattersall uses different kinds of open data sources many times a week. “I’m often using Statistics Finland’s Annual national accounts. It’s a really delicious data collection.”

Ten years ago, the data openings were mainly large files. “Now we are talking a lot about application programming interfaces”, notes Poikola.

Antti Poikola is also working with open data at least on a weekly basis. Promoting the prerequisites for a new kind of data economy is an important part of the supervision of the interests at Technology Industries of Finland. “The Technology Industries of Finland is really trying to further, for example, the creation of public administration interfaces.”

Asta Manninen guesses that during the next decade, the world of open data will once again take some giant steps. “Opening data is then very easy, as is the using of it”, ponders Manninen.

Tanja Lahti is also certain that data systems and technology have developed in an increasingly open direction. “The most important public data can be utilised by anyone and they are interoperable. At that point, APIs are an everyday thing”, contemplates Tanja Lahti.

“We should not expect a billion euro turnover from opening data. I think it is a good thing, which one day can produce significant benefits for society”, says Tattersall.

The first decade of open data in Finland was celebrated with Helsinki Region Infoshare, Open Knowledge Finland and avoindata.fi on 8-10th October 2019. During the three days there were several workshops and celebration gala at the Helsinki City Hall on 10th October.

Translation: Henrik Andersson